[ 27 July 2017, 03:30, MAA ]

As the plane landed on the tarmac, my introduction to both Chennai and Monsoon Assemblages had officially begun. For the past two years, I’ve been based in Jakarta, Indonesia–a neighbouring coastal megacity in Southeast Asia. On approach from the air, the glow of ship lights in the Jakarta Bay is the first hint of land as one descends from the clouds towards the city–a greeting that is matched by other coastal cities in the region. However, as I sleepily peered out the window searching for the Bay of Bengal, my eyes found nothing but land.

Of the many lessons from Jakarta, one is central to them all: the documented–often understood and drawn–geography of a place might be radically different to the experienced or depicted geography of a place. Stories and images conjured from the perspective of European Colonial histories of South and Southeast Asia, tend to orient cities to the sea–as points of extraction, collection, and departure. In the case of Jakarta, its history as the Dutch-ruled Batavia, tends to bend the city’s image and identity to the coast; although, many Betawi people (native Jakartans) still living in the city today identify with the river, not the coast (1). Evidence of the experienced orientation of the city towards the river(s) can be seen across the metropolis in both everyday activity and the patchwork of formal and informal urban fabrics–the story of the city’s character and creation. As I waited for my luggage, I wondered what gaps and overlaps I might find between the documented and depicted in Chennai. In terms of the city’s rhythms and the realities of day-to-day life, what role(s) does the Bay of Bengal, the rivers that traverse the city, and the waterbodies that dot the landscape play in the atmospheric forces of the monsoon in both the imaginary and real construction of the city?

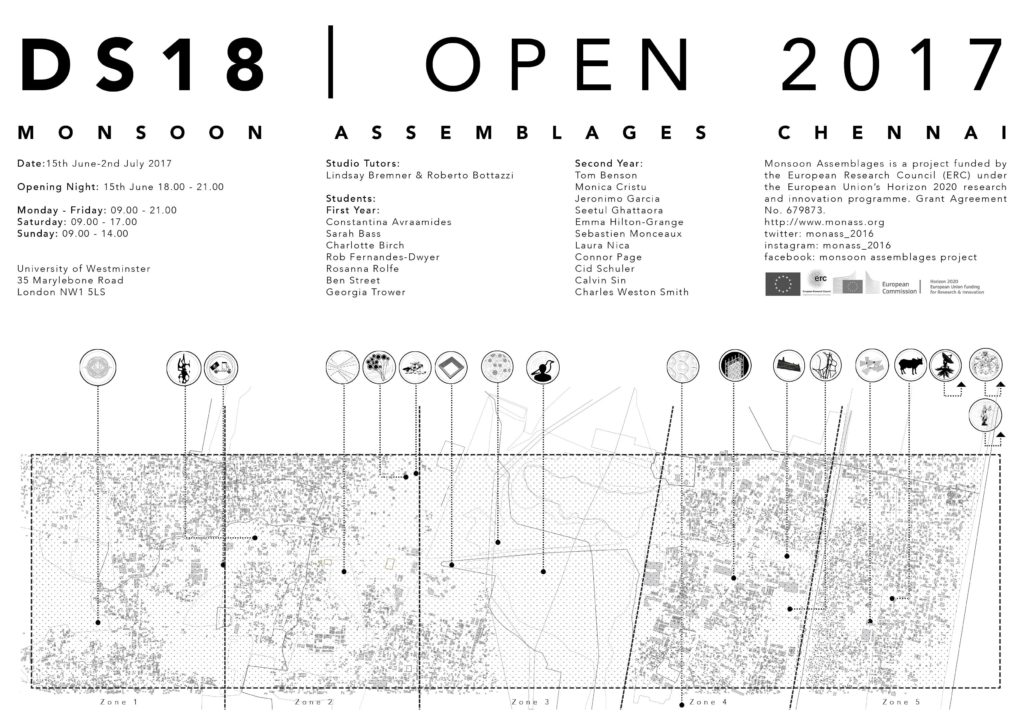

Trained as an architect, urbanist, and landscape architect, when beginning a new project I start by defining a frame within which the primary characters will perform–or rather, a frame within which I can uncover the characters that will bring a project into focus. Both Lindsay and Beth had been in Chennai for several weeks before my arrival and I was anxious to hear about and see the sites of their work so as to consider it’s positioning in this new landscape. After lengthy conversations with Lindsay about scales of encroachment on Chennai’s water bodies and visiting Perungudi Lake with Beth, it was clear that these investigations were tugging at critical components of both construction and culture within this monsoonal topography. Over the course of the next few weeks, a series of events would unfold bringing into focus a launching point for my investigations into Chennai and Monsoon Assemblages.

[ 3 August 2017 ]

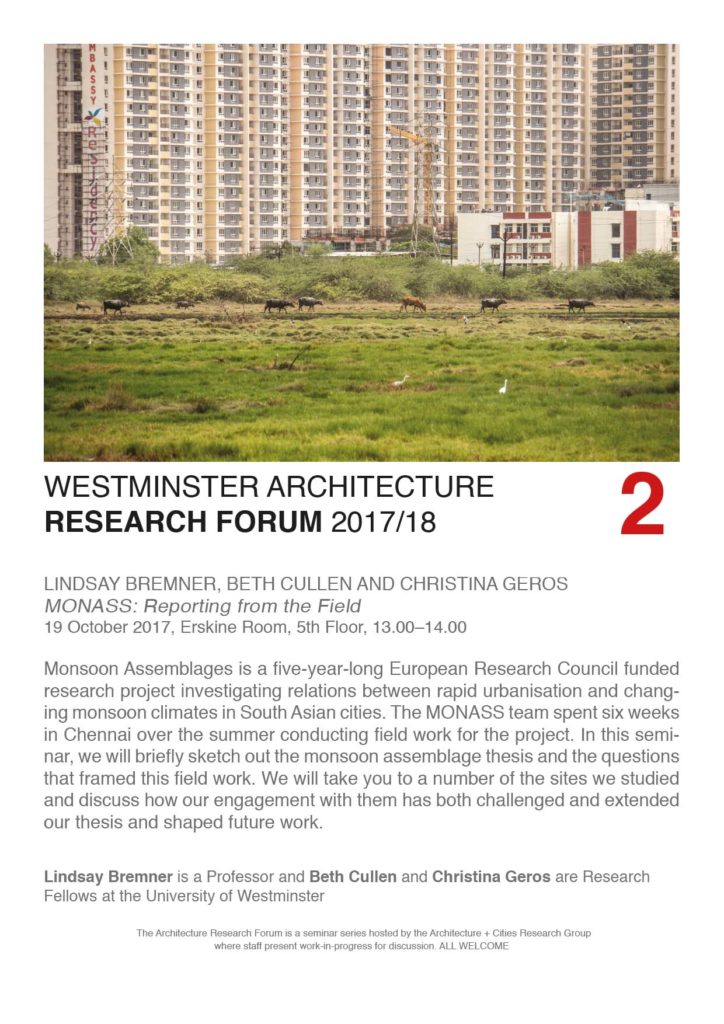

Staying only a short walk from Elliot’s Beach, we ventured out one day to see the Bay of Bengal. It was beautiful, peaceful, lively, and under construction. Marching into the sea, enormous block buildings ushered the shifting sands of the shoreline into geometries of control and stability. Unapologetically exposed under the brutal sun and the wide-open skies, the enormous scale of the development felt overbearing and insignificant in this space of transition between land and sea.

[ 4 August 2017 ]

The next morning, we thought we’d catch the sunrise and document activity around the Bay at dawn.

[ 1 August 2017 ]

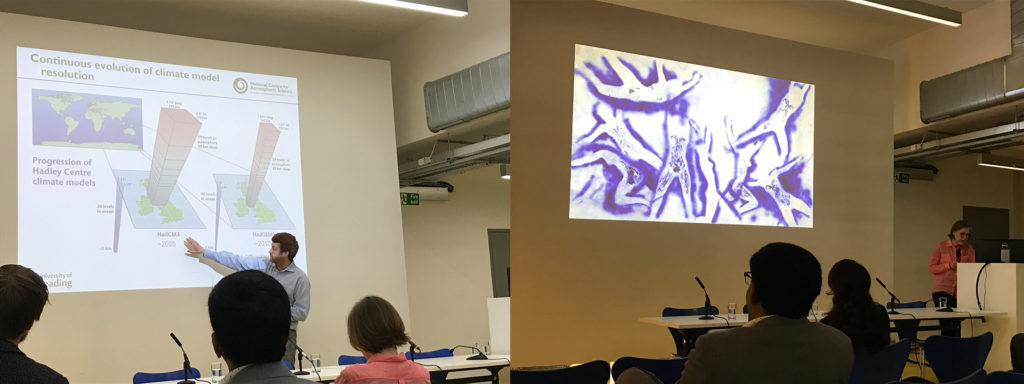

Watching the sun reveal the form of clouds rolling in over the waves of the sea, I was reminded of the instruments of measure used at the Chennai Meteorological (MET) Office. The Regional Meteorological Centre in Chennai is one of six regional centres for India and one of the first modern weather observatories in the eastern part of the subcontinent. Weather forecasts are loaded with satellite images, doppler radar, and digital interfaces, making it seem like some mysterious science reserved for super humans and computers; in reality, the instruments used to measure weather–temperature, air pressure, humidity, wind direction and velocity–are incredibly simple even at the MET Office.

[ 10 August 2017 ]

A week later I interviewed Pradeep John, a Chennai-based weather blogger about his particular spin on reading meteorological data against the Tamil Nadu landscape. Pradeep John works with data and is intimately familiar with the histories of Chennai’s waterbodies and terrain through their statistics. He has nearly a quarter of a million (and counting) followers on Facebook and many consider him to be the most accurate weather forecaster of Chennai. While riddled with interesting facts and stories, the most poignant moments in our conversation centred on Pradeep John’s assertion that the accuracy of a weather forecast is about interpretation–not only data–and that interpretation is about the human body, memory, and experience. Our experience of, and within, the space between landscape and atmosphere is  visceral, not only factual.

visceral, not only factual.

[ 11 August 2017 ]

The next day I took a drive south, along the Buckingham Canal towards Pondicherry. Nearing Pondicherry, the blinding reflection of the salt flats whose stunning relationship between sky and sea are hard to miss.

[ 14 August 2017 ]

Pradeep John had mentioned that large reservoirs in and around Chennai were “wet spots”–meaning that, according to the data, these places not only held more rainfall, but received more rainfall (about 20%), than the rest of the city. Chembarambakkan Lake–that largest reservoir in Chennai–is one of these “wet spots.” So, Beth and I took an excursion across the city–via the IT Corridor, across the Pallikaranai Marsh–to see Cherambarambakkan. Different from the salt flats, but undeniably tied to the atmosphere, this place seemed to speak of something far beyond, yet intrinsic, to the land Chennai occupies.

[ 14 October 2017 ]

Defining a frame is an ongoing process that requires a constant refocusing of one’s tools and perspectives. Now back in London, drawing through the relationships and spaces revealed during the fieldwork, I can see that all of my previous experience is informing the search–a little bit of sea, a little bit of sky, a river here, and a lake there.

Something dwells here. What it is, I do not know / But it’s grace brings tears to my eyes (2).

(1) Interview with Evi Mariani Sofian, journalist and urban studies scholar in Jakarta, on 2 June 2017.

(2) Saigyō, from Saigyō hoshi kashu